Report from the Divine Strake "hearings."

Ursula Zwick was shocked at what she saw: Security guards descending on a man at a public meeting to physically remove him from the room for the heretical act of asking a question: “Who in the room is against Divine Strake?” The crowd’s response: a thunderous “We are!”

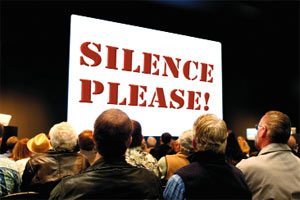

Security guards in plainclothes pounced, physically escorting Kevin Donahue from the room for “alarming the audience” and “disrupting” the proceedings. The proceedings in this case entailed a public meeting hosted by the Department of Defense’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency and the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration – the federal agencies who plan to explode a 700-ton bomb at the Nevada Test Site this spring.

“I thought this was a public meeting,” Donahue said as an officer grabbed his arm.

“This is NOT a public forum,” the officer shouted, a refrain he repeated as stunned onlookers asked the same question.

“I’ve seen something like this when I grew up in Communist Poland,” said Zwick. “But I’ve never seen something like this in America. This man gave us our only opportunity to voice our dissent. If we have the ambition to promote democracy in other countries like Iraq, we should practice it at home.”

The incident only confirmed suspicions that what had been billed as public meetings by the DTRA and NNSA were not the public hearings that had been promised to congressional delegations in Utah, Nevada and Idaho.

Two signs posted at the Salt Lake City event dubbed it a “public information session,” a twist of phrasing whose meaning was simple — No public comment would be welcome.

The event, in fact, was more akin to a high school science fair: posters and charts on easels at tables manned by representatives assigned to talk about various technical aspects of Divine Strake.

The staged event included neither an official welcome nor presentation, just 12 tables lined up against the walls of the Grand America Imperial Ballroom.

Rep. Jim Matheson and Sen. Orrin Hatch, who both sent staffers to the event, fired off a letter demanding real hearings to James Tegnelia, director of the DTRA. Idaho didn’t get its dog and pony show until the entire Idaho delegation sent Tegnelia a letter demanding an event in the state.

Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman, forewarned by activists about the format of the meetings, sagely scheduled his own hearings in late January, providing citizens both a podium and a microphone to voice their concerns. Comments were transcribed and submitted with the governor’s own written comments to DTRA.

In America, we hold dear our right to freely express our concerns, particularly when it comes to government policies and activities that could be detrimental to our health. We trust that we will have a say in the decision-making process.

Sadly, however, most public hearings — call them meetings, forums or information sessions; it’s all a matter of semantics — are not true opportunities for citizen participation. Nor are agencies holding the hearings truly interested in hearing from the public, let alone acting on their concerns. Too often, the public is viewed as an inconvenient, irrational nuisance to be appeased, convinced and co-opted, or — as a matter of last resort — ignored.

For Danielle Endres, a University of Utah professor of communication who specializes in the public hearing process, the January meeting was a textbook case of how public participation is discouraged.

The meeting was announced two days before Christmas — when most people would be too distracted to notice. The public would be allowed to comment only on the scientific and technical aspects of a 240-page environmental assessment.

The location was to be the Energy Solutions arena, a mammoth facility in which even a healthy crowd would be dwarfed. The night before the meeting, organizers suddenly announced that the venue had been changed to the Grand America Hotel, creating more confusion.

Endres, whose research has documented “the guise of deliberation,” says, “The process is flawed from the start. Public hearings are created in ways that seem like they are democratic and will involve public participation. In reality, hearings are generally held only after the decisions have already been made.”

Her research has found the Department of Energy to be “one of the worst” offenders. “They’re very resistant to making any changes to their policy. Public meetings are just another check-off for them. They can say, ‘Now that we’ve done our democratic deed for the day, we can continue with the proposal we’ve wanted all along.”

She notes that most hearings are held in response to scientific and technical documents, as was the case with the Divine Strake meeting. “This is problematic because it reinforces the superiority of scientific and technical knowledge,” she says. “Of course those are important, but that means that health, cultural, social or economic arguments can be easily dismissed.”

Focusing on the science and technology also discourages many people from attending hearings, because they think they lack the expertise to comment. Often, she says, agencies expect people to read a 2,000-page report and come up with arguments, which is intimidating and not always possible.

In reading transcripts of hearings, Endres has found that even when citizens make sound scientific arguments, they preface their statements with “I’m not a scientist.” She says, “That reflects the intimidation. We do have the skills to be able to comment on the science.”

She has also seen the “national interest” used to outweigh all other arguments. “I think that’s what’s happening with Divine Strake,” she says. “In several conversations I had at the various stations, an underlying assumption was that Divine Strake is in the national interest. When you state national interest as an argument, it’s almost impossible for the public to argue against it, because they can say, ‘this is just a small population of Utah’ — the same argument used during nuclear testing.”

And what happens to the public comment that is gathered? “They may compile it and make documents that respond to it, but from what I’ve seen it really doesn’t get incorporated into the decision,” says Endres.

Ultimately, she says, we must reform the current model of public participation to create a system where the public is invited to the table from the start and where it is included in the decision-making process.

Despite problems inherent in the system, she says, public hearings can still be a valuable tool, particularly in encouraging collective action among those who attend.

“The man who spoke up was great,” she says. “It became a media event that people reported on. You may not get your voice heard to the DOE or other departments, but you have another audience, which is the public.”

That public includes elected officials who can intervene through legislation. “Most decisions eventually are voted on, so involving elected officials is critical,” she says, reminding that Divine Strake was postponed last year due to public protest. “We definitely can make a difference if we make enough noise, talk to the right people and bring public pressure to bear.”

Kevin Donahue, the man who dared ask the 200-plus crowd at the Grand America if they were against Divine Strake, feels his constitutional rights were denied merely for “addressing my community.” He has contacted the ACLU, attorneys and his elected representatives to see what recourse is available to him. “It was a meeting called by federal agencies. Doesn’t that constitute a public meeting? Or do my constitutional rights end at the hotel door?”

And after watching Donahue removed from the ballroom that night, Ursula Zwick, who left her native Poland for the land of the free, is still wondering what kind of freedom America really enjoys.

Salt Lake City writer Mary Dickson is a downwinder whose play, “Exposed,” will be produced by Plan B Theatre next October.