Protect your joints, build stability

Instagram may currently dominate and define 21st-century yoga’s outward image, but social media didn’t invent yoga photography. As long ago as the 1960s I remember gaping at photos of loincloth-clad yogis staring wide-eyed—and rather forbiddingly—at the camera, balancing on their hands with one ankle hooked behind their neck and the other leg thrust out toward the camera.

By the 1980s, asana photos became a bit friendlier and more mainstream with photos of lanky, leotard-clad women practicing maybe-next-lifetime poses such as King Dancer on a sunset-drenched beach. It is arguable that yoga photography, from the cover photos on yoga magazines to the proliferation of yoga selfies on social media, has had a hand in defining yoga in the popular imagination.

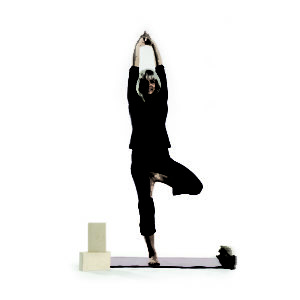

The common denominator in asana photography from its early days to today is the proliferation of images that depict people either performing the most extreme poses, or performing more pedestrian poses in their most extreme manifestations. We define practitioners who can perform the most extreme poses as “advanced” and those whose bodies just won’t go there as perpetual beginners.

This is a fallacy, one that has borne unfortunate consequences. We are all structurally different. Some people’s bodies will move to these extremes in the first months, or even days, of practice. This doesn’t make them advanced. It simply means they came into the world with joints that move further before bone articulates with bone. Some people whose bodies readily perform fancy poses may have been born with shallower joints or pathologically loose ligaments (joint hypermobility syndrome). Or maybe they’ve already stretched their ligaments to the point where they’re overly lax. This is not optimal. And yet, these images are burned into our consciousness as the peaks we could achieve—if only we’d try a little harder.

The normalization—and admiration—of hypermobility has given rise to a proliferation of classes and workshops dedicated to “hip opening.” It’s true that as we age, maintaining flexibility in our hip joints—as well as the knee, ankle, shoulder, elbow, wrist, finger, toe and vertebral joints—is important. If we don’t move our joints regularly, the path of least resistance will lead to decreasing mobility. But over time, constantly pushing our joints to their end ranges can pro

duce the exact opposite of hip opening—the degeneration of the joint capsule, tight muscles that must do the stabilizing work of our ligaments, and the development of movement-limiting bone spurs.

Pushing our joints to their end ranges also potentially overstretches ligaments, which, as we now know, do not spring back to their original length. Ligamentous tissue does have a very limited amount of elasticity (the ability to recover from a stretching). But ligaments are elastic only in the first tiny bit of a stretch. Once they are stretched beyond their limit, they are permanently elongated and can no longer effectively stabilize the joint.

In her 2016 YogaUOnline article “‘Hip Openers’ in Yoga? Please, Let’s Stop the Madness,” physical therapist Dr. Ginger Garner discusses the perils of focusing too much on hip opening: “It is not helpful that many people think they only need to ‘stretch out a tight hip,’ when in fact, they have bony and structural idiosyncrasies that prevent them from ever moving into certain yoga postures. Sure, soft tissue structures can be inhibiting hip range of motion but rarely is it helpful to put the bony parts of the hip in vulnerable end ranges. We aren’t going to force or bully the tissue to deform under extreme tensile loads, and 99% of the time, the average person (unless you are an elite athlete) isn’t going to be able to stabilize yoga postures in end ranges of motion. Typically, the capsule, ligaments and cartilage will bear the load, including the bony structures, and they have a finite shelf life for handling that kind of adverse stress.”

If you take a closer look at photos featuring extreme poses, you can see that most of these poses are impossible to achieve without forcing our joints into their vulnerable end ranges. Given the risks of repeatedly pushing our joints into their end ranges, how can extreme poses, or pushing our bodies to extremes in more widely accessible poses, possibly contribute to our ability to move through our lives with ease?

Practitioners who are naturally hypermobile need to take more, rather than less, care with their joints. Flexible people often believe they need to push further into a pose in order to feel sensation. Because of the pervasive belief that we must “feel something” in order to benefit from practicing a pose, hypermobile people are more likely to push into their joints’ vulnerable end ranges. For the past 10 years or so, I’ve actually been practicing staying well inside my end range in every pose. In addition to protecting my joints, practicing this way helps me build the stability my body lacks.

Asana practice is not simply about becoming ever more flexible. Alistair Shearer’s translation of Sutra 2.46 in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras says: “The physical posture should be steady and comfortable.” Other translations use opposites such as “firm and soft,” “steady and easy,” and “stable and comfortable.” To me this implies that practice is about balancing stability and flexibility, rather than pushing flexibility to the exclusion of stability.

Everyone’s end ranges will look different. Even if your body will never rock those iconic fancy poses, it’s still important to be mindful of staying within your end range in order to build both stability and mobility.

Here are some suggestions:

- Check your breathing. The quality of your breath—its rate, depth, and ease—is a reliable inner guide as to the quality of your effort. If your breathing is restricted, you’re pushing too hard. As you inhale and exhale, your body naturally oscillates. When we push into our extreme edge, our bodies tighten and can’t oscillate with the breath. Set aside your ideas about what a pose “should” look like. Relax into where you are. This pose, right now, is where the yoga is. Allow the internal breath movement to guide you into your asana.

- Stay inside your edge. Staying 5-10% inside your end range will help promote stability and protect your joints, in addition to allowing your breath to move your body. This is especially important for people whose joints are on the looser side. Tempting as it is for us “flexies” to take it to the limit, pushing our end ranges creates imbalance and can damage our joint structures.

- While you’re in an asana, orient your intention toward producing continuity through your joints. When you push into your joints’ end ranges, the extended side of the joint will likely feel stretching sensations, while the flexed side of the joint feels compressed. For example, extend your arm outward from the shoulder, 90 degrees to your torso. Stretch your arm backward as far as it will go. You will likely feel stretching sensation in the front of the joint and compression in the back of the joint. Move your arm forward until the front and back of your joint feel equally open. This principle applies to all your joints. As you practice, scan your joints. If you feel compression on the flexed side of the joint, you are likely pushing into your end range.

The “full expression”

“Full expression” is a widely spoken term in yoga circles. When a teacher encourages those who can to move into the full expression of a pose, it’s usually an invitation to explore the most extreme expression of a pose. In terms of yoga’s deeper aim—the settling of the mind into silence—there’s another way to think about what full expression could mean.

According to Shearer’s translation of Sutra 2.47, asana practice is mastered when “all effort is relaxed and the mind is absorbed in the Infinite.” Full expression of an asana happens when we are both stable and at ease, when we are no longer struggling against the asana as it is. It arises when the outward expression of our pose is in harmony with the inner movement of our breath and when we have invested our full attention into the sensations arising as we move and breathe. Full expression is not dependent on what a pose looks like. Rather, it depends on our physical/mental/emotional investment into each moment of the living, breathing process that is asana practice.

A version of this article appeared in Hip-Healthy Asana, by Charlotte Bell, © 2018 Charlotte Bell. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc.