White supremacist literature becomes nationally acclaimed human rights art exhibit; in Utah now through September 3.

In 2003, a member of a white supremacist group in Montana defected, taking with him a massive collection of the group’s literature and correspondence. In return for help getting out of the state, he turned the materials over to the Montana Human Rights Network (MHRN).

MHRN and the Holter Museum of Art in Helena, Montana turned two storage lockers full of vitriol from one of the most violent hate groups in the U.S. into a riveting art exhibition. Speaking Volumes|Transforming Hate has been touring the country for over a decade and recently arrived in Utah for an eight-month stay.

I sat down to talk with Katie Knight, an art and photography teacher at Helena High School and the former curator for the Holter Museum of Art in Helena who has been the curator of Speaking Volumes since it began in 2004.

MM: Speaking Volumes has such a strange and fascinating backstory. Can you explain how it went from being a collection of white supremacist books to a nationally acclaimed multicultural art exhibition?

KK: The Northwest part of our country is, historically, one of the least diverse areas; that may be the main reason white supremacists had the idea that they could take some political power.

This group was originally called World Church of the Creator but renamed themselves the Creativity Movement. One member had land in the northwest part of the state where the organization was holding their rallies and demonstrations. Their agenda has been to exterminate all Jews and kill the “mud races,” which would be what they call people of color. Whenever they would have a rally, the Montana Human Rights Network would have a counter protest proclaiming love and justice. So, the Creativity Movement organizers were well aware of the Montana Human Rights Network.

The Creativity Movement is a pretty fractured, dysfunctional group. One of the leaders decided he wanted to put some distance between himself and his colleagues. He contacted Ken Toole and Christine Kaufmann, who were then the directors of the Montana Human Rights Network, and said, “I’d like to sell you 4,900 books and a bunch of original correspondence. I need $300 to get out of the state.”

The books were written by Ben Klassen, founder of the Church of the Creator, and they have provided ideological continuity for the group, allowing it to survive through tumultuous leadership changes while also providing an income stream via internet sales. Ken and Christine did a little research because they did not want to buy stolen property, although they were quite eager to acquire the books.

They found out that a federal judge had awarded all of the assets of the Creativity Movement to the Southern Poverty Law Center in a lawsuit, which gave Ken and Christine the go ahead to acquire this material. A year later, in 2004, MHRN sent out 500 books to national research libraries and organizations that monitor hate group activity. They still had over 3,500 books and didn’t know what to do with them until Ken Toole’s son said, “How about we use them to make art?” Not too long after that, I became involved with the project.

MM: What was your role at this point?

MM: What was your role at this point?

KK: I was the curator at the Holter Museum of Art in Helena, but I have been active with the Human Rights Network as a volunteer since I moved to Helena in 1999. When I heard about these books, my imagination went wild. I thought it was a rare opportunity for artists to actually put their hands all on the same material simultaneously and then move in their individual directions in transforming hate. We worked for two and a half years to organize the exhibition. The show is a combination invitational and juried show so we were able to include some high-profile artists who had spent their lives focusing on social justice content.

MM: Has there been any reaction from the Creativity Movement or its affiliated groups?

KK: We were anxious leading up to the show. We were prepared to activate a community-wide network if someone was threatened. But we really haven’t seen much since we opened the show.

MM: I’m wondering what you saw as the lifespan of this project. Did you ever think that it would have the duration that it has had?

KK: No, no, I did not know that 14 years later I’d still be working on it. When we opened the show at the Holter in January 2008, Barrack Obama was being inaugurated and there was a certain kind of optimism and a feeling of triumph over racism. But, in fact, what happened that very first year was a multiplication of hate groups. They were angry about immigration.

And there are actually people with economic resources who may be using this movement to divide people and to gain wealth. Actually, the author Ben Klassen self-published all those books with the profits from his invention of the electric can-opener—a little bit of trivia there. Anyway, no, I didn’t anticipate the direction things would take. It’s extremely disappointing, what’s happening now in terms of social justice.

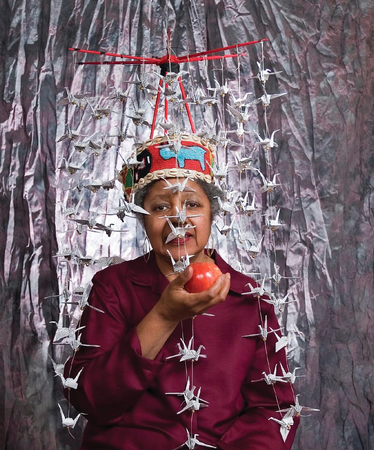

MM: I want to talk more specifically about some of the artwork in the exhibit. In other conversations, you’ve referred to Jean Grosser’s piece, Shrines, as kind of a centerpiece of the project, at least from your point of view. Can you explain why you feel that way about that work?

KK: In part, it is because it directly addresses the content of the books and their anti-Semitism. Grosser made eight beautiful little memorials that I think are extremely direct and touching. You have a portrait of the individual being memorialized—these people are relatives of hers who died in the Holocaust as well as some who survived. She put them into a little shrine with an artifact or object—a dreidel or a book, something of cultural significance to the Jewish people. Then she covered the shrines with pages from the books. Their edges have been burned. So, they aren’t really legible pages, but she’s transformed them physically. I think it’s a really poignant, intense piece that is historical and also relevant today. She is a witness with this work. This is a storytelling piece. It’s a metaphoric piece. It functions in a lot of different ways.

MM: Some of these pieces are working through humor. I’m thinking in particular of the work from Enrique Chagoya, Charles Gut, and Jim Riswold. With such heavy material, and such high stakes in this work, what role do you think humor plays in encouraging empathy in viewers and encouraging people to support social justice movements?

KK: First of all, I think the work represents a lot of different strategies, which is part of what makes it accessible to so many different people. Different pieces will appeal to different personalities. But humor was an incredible survival tool for a lot of historically oppressed groups who have used it to turn around that power relationship and take control of their own identity.

Enrique Chagoya is a humorist who has a strong postmodern, intellectualist background. So, The Pastoral or Arcadian State: An Illegal Alien’s Guide to Greater America is based on The Jolly Flatboatmen by George Caleb Bingham. His work is also autobiographical. That’s him who’s been flayed. He’s skinless and dancing in the middle there with his Mexican sombrero. There’s just so much detail in his work. You can’t get it all. He’s also referencing the Thomas Cole work The Arcadian or Pastoral State, which is one of the five paintings in the series titled The Decline of Empire. The postmodern layering in his work is characteristic of someone with a really sophisticated academic background. But you don’t necessarily have to know any of this to smile when you see the work.

As for Riswold, he has a great TED Talk describing how Adolf Hitler saved his life. He was a top designer in California, and he was diagnosed with leukemia. He took time off for treatment and during that time he started finding these crazy Hitler toys and then began juxtaposing them against more conventional toys. He was shocked that there were people actually collecting these little Hitler models, so he put them with the other toys to make fun of them.

As for Riswold, he has a great TED Talk describing how Adolf Hitler saved his life. He was a top designer in California, and he was diagnosed with leukemia. He took time off for treatment and during that time he started finding these crazy Hitler toys and then began juxtaposing them against more conventional toys. He was shocked that there were people actually collecting these little Hitler models, so he put them with the other toys to make fun of them.

MM: During our opening night in Springville there were Cub Scout troops in the museum. One group turned the corner into the exhibit and saw those photographs and they immediately started tittering and whispering to one another. Their leader said “hey guys, we’re here to think about this stuff” and started asking them some tough questions. That made me wonder what tools you employ in working with children. This is really tough material for parents, for teachers, for anybody to deal with. So, how do you engage children and young adults in ways that are productive?

KK: When we opened this show in Helena, we made it our third grade field trip, so every third grader in Helena came to see the show and then they created their own work.

One of the ways that I really like to engage audiences is with Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS). It’s really just asking basic questions. I could talk a lot about the art but it’s more meaningful to get a group of young people involved in thinking and sharing their perceptions. So, we ask, “What’s going on here?” and get people to make an observation. Two really great pieces for VTS are Jane Waggoner Deschner’s The Way Things Go, and Don’t and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith & Neil Ambrose-Smith’s Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes, both of which have a lot of ambiguity. You ask “what’s going on here” and it’s important to follow up with another question such as “what makes you say that?” People jump to conclusions and you really want to keep it connected to the art, read what’s going on in the art. Then you ask “what else can we find” to keep the conversation going and keep digging. VTS is a great way to gather around work and get young people thinking. It’s not important that they interpret it the same way that I do.

One of the ways that I really like to engage audiences is with Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS). It’s really just asking basic questions. I could talk a lot about the art but it’s more meaningful to get a group of young people involved in thinking and sharing their perceptions. So, we ask, “What’s going on here?” and get people to make an observation. Two really great pieces for VTS are Jane Waggoner Deschner’s The Way Things Go, and Don’t and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith & Neil Ambrose-Smith’s Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes, both of which have a lot of ambiguity. You ask “what’s going on here” and it’s important to follow up with another question such as “what makes you say that?” People jump to conclusions and you really want to keep it connected to the art, read what’s going on in the art. Then you ask “what else can we find” to keep the conversation going and keep digging. VTS is a great way to gather around work and get young people thinking. It’s not important that they interpret it the same way that I do.

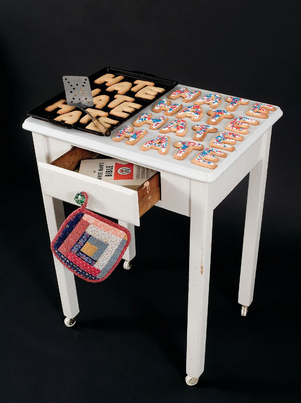

MM: So many of these works employ everyday objects such as tables or a tire swing— I’m thinking of works like Strange Fruit, Superior and Cooling Table which all engage with these kinds of objects that are infused with a rhetoric and historical context that is so powerful. A child looking at a tire swing isn’t likely to think twice about it. It takes a more nuanced eye to explain that a tire swing isn’t typically secured with a noose. The phrase “banality of evil” comes to mind here. How do you think that notion functions within this project?

KK: I think those pieces tie in to the idea that prejudice is taught at home from an early age, That’s obviously one thing that the “HATE cookies” are saying. The table is intended to be a library table, and with that book there, you’re invited to sit down and read. But you could become entrapped. You’re younger than me, so you probably didn’t grow up on the movie South Pacific. There’s a song in there called “You’ve Got to be Carefully Taught.” You’ve got to be carefully taught by your parents to hate and fear others. Initially it’s a self-preservation tactic.

KK: I think those pieces tie in to the idea that prejudice is taught at home from an early age, That’s obviously one thing that the “HATE cookies” are saying. The table is intended to be a library table, and with that book there, you’re invited to sit down and read. But you could become entrapped. You’re younger than me, so you probably didn’t grow up on the movie South Pacific. There’s a song in there called “You’ve Got to be Carefully Taught.” You’ve got to be carefully taught by your parents to hate and fear others. Initially it’s a self-preservation tactic.

But one thing I like to do when I’m doing educational work with this show is to distinguish between prejudice —which we all learn and seems to be part of human nature, not necessarily a desirable part, though —and discrimination, which is an institutionalized system of oppression that gives more opportunity to some groups over others.

But those pieces you mentioned, they’re very accessible, especially Cooling Table. I hope the cookies looked good for you guys. We’ve had to make so many replacement cookies. Even though Miguel Guillen coated them with wax or with acrylic, they still smelled so good. At the very first show, somebody took a bite out of one. I had to have my mother make us new hate cookies. It was a little uncomfortable for her. But it was an emergency, you know.

MM: Do you think the approach to this project would be different if this were all coming to fruition now?

KK: I think the artists would likely make very different art. Also, things are increasingly precarious for non-profit organizations including arts organizations; their economic survival is increasingly precarious. So, there might be a little more caution there.

At the time, I was amazed how many Montana museums and nonprofit galleries booked this show. It was the longest, largest tour that I’d ever seen in the state or through the Museum and Art Gallery Directors Association of Montana. Now, I would hope that it would be equally or more successful. There’s certainly an urgency and there’s also a lot more artists who have become politicized now than there were before.

MM: What has been your favorite part of the curatorial process for this project?

MM: What has been your favorite part of the curatorial process for this project?

KK: To me, it’s the human interactions. I have loved getting to know so many of these artists whose stories I now really carry in my consciousness. But what also gets me reenergized is working with community groups. Tuesday evening I sat down with people from the YWCA, the library, the school, the art museum, the Human Rights Network and the performing arts center in Helena. We’re all brainstorming and making plans for when this show reopens here later this year.

Having everyone bring their expertise and passion and collaborate on this community dialogue in which our goal is to be a more just society and to humanize our young people and to sensitize them to the humanity of everyone—that really recharges my batteries. When you’re alone at home trying to manage the nuts and the bolts and the trucks and the lifts and contracts and all that stuff, that’s not exciting. But collaborating on the programming is always really inspirational. It’s what keeps me going.

Speaking Volumes: Transforming Hate is sponsored by Utah Humanities in partnership with the Springville Museum of Art and the Ogden Union Station Foundation with support from the Utah Division of Arts & Museums and the B.W. Bastion Foundation. Through June 2 at Springville Museum of Art, and June 15-September 3 at Ogden’s Union Station. For more information and related events: www.utahhumanities.org, www.smofa.org/speaking-volumes.php or www.speakingvolumes.net

Michael McLane is the director of the Center for the Book at Utah Humanities. He is a graduate of the Environmental Humanities program at the University of Utah and is an editor with the literary journals saltfront: studies in human habit(at) and Sugar House Review. He wrote about Warm Springs Park in the December 2017 issue of CATALYST.