by John deJong

Can we have a sensibly located soccer complex and save the last remaining strets of riparian habitat along the Jordan in SLC? Ask your city council member.

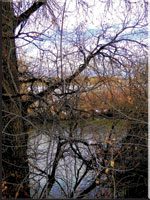

It’s not much to look at—just another piece of tired bottomland on the Jordan River. Viewed from the west on a smoggy, inversion-shrouded Christmas morning, with the fumes and vapors from the Chevron refinery rising before the gravel pit-scarred face of the Wasatch Fault, it looks like a backdrop for a 21st century staging of Dante’s Inferno. The random flights of flocks of birds add a computer-generated-graphic effect James Cameron would be proud of. It’s an unlikely site for a soccer game.

It’s not much to look at—just another piece of tired bottomland on the Jordan River. Viewed from the west on a smoggy, inversion-shrouded Christmas morning, with the fumes and vapors from the Chevron refinery rising before the gravel pit-scarred face of the Wasatch Fault, it looks like a backdrop for a 21st century staging of Dante’s Inferno. The random flights of flocks of birds add a computer-generated-graphic effect James Cameron would be proud of. It’s an unlikely site for a soccer game.

But a 13-field soccer complex is what Salt Lake City is planning for 160 acres located between the Jordan River and I-215, just east of the airport.

It’s not much to look at—just another piece of tired bottomland on the Jordan River. Viewed from the west on a smoggy, inversion-shrouded Christmas morning, with the fumes and vapors from the Chevron refinery rising before the gravel pit-scarred face of the Wasatch Fault, it looks like a backdrop for a 21st century staging of Dante’s Inferno. The random flights of flocks of birds add a computer-generated-graphic effect James Cameron would be proud of. It’s an unlikely site for a soccer game.

But a 13-field soccer complex is what Salt Lake City is planning for 160 acres located between the Jordan River and I-215, just east of the airport.

The dream began in the glow of the 2002 Olympics. Mega sports complexes were the rage. Soccer is a popular sport and soccer fields are at a premium all along the Wasatch Front. The idea of a major soccer complex with upwards of 25 soccer fields to be built on some unused piece of land was irresistable. And, for about $600,000 per field, a good deal.

Never mind that there was already one major soccer complex in the valley. “It’s way out in West Jordan!” you keen. You have a point. Would soccer fields in the far northwest corner of the City be much of an improvement?

Look again. It’s not just another piece of tired bottomland on the Jordan River. It’s the last piece of undeveloped bottomland along Salt Lake City’s portion of the Jordan River. (The city has owned the property since October but it’s not technically in the city, as it hasn’t been annexed by yet.)

Most of the land along the Jordan River in Salt Lake City has been reduced to a paved jogging path. The overgrown backyards of businesses and residences abutting the river provide the majority of the riparian area. On the publicly owned stretches, occasional thickets of cattails and weed trees, where they’ve been allowed to grow for a season or three, mar the mowed-lawn-down-to-the-river’s-edge aesthetic. Frederick Olmstead, father of “natural” parks, would be appalled.

The Jordan River is part of an international flyway that provides habitat for millions of resident and migratory birds. This continuous string of bird-friendly habitat, where birds can feed, mate and nest, is essentially interrupted or non-existent along Salt Lake City’s portion of the Jordan River.

The Powers That Be in City Hall, pre-dating the Becker administration and some current City Council members, have gamed the system to push the soccer complex. The vote on Proposition 5 in 2003 that authorized the $15.3 million bond to build the soccer complex was 20,475 “for,” 19,454 “against”—not an overwhelming mandate, even considering the 48% turnout. The City has now determined that “the original $22.8 million estimated budget was underestimated.” Some might consider that grounds for a do-over of the bond election or at least a penalty kick.

{quotes}The reason this soccer complex is “long awaited” is that it took nearly four years to find a donor to come up with the $7.5 million match required by the bond. The local soccer community never stepped up with any funds. The match came from Real Salt Lake—nice move. It gets its name on a couple more venues while salving the wound it inflicted on Salt Lake City when it built its soccer stadium in Sandy.{/quotes}

In the briefing document for the City Council, the section titled “Public Process” might as well be called “Public Pastiche.” The document, put forth by director of public services Rick Graham, implies the public has known all along about the preferred location of the proposed sports complex. For those who carefully studied their voter information packet, this is true. But we have found few public references.

The land comes to the city from the state by way of the noble, if misconstruable, 1965 Land and Water Conservation Fund Act that provides for open space—not rivers and streams and forests and fields but golf courses and soccer fields and parking lots and retail concessions, according to the City’s reading of the act. Apparently the City doesn’t believe it’s possible to turn the site into a really great riparian area. Nonetheless, it would be possible, just by tearing down the berms, to allow the Jordan River to have its way and restore itself, damn the Corp of Engineers.

Economic engine or caboose?

In modern urban planning parlance the Jordan River is, among other things, an “economic amenity.”

The original justification for using tax dollars to pay for this project was that it would create economic activity by attracting local, regional and national soccer tournaments which would generate tax revenue, which would more than repay the good taxpayers of Salt Lake City.

As the size of the project has been refined from the blasé “up to 25 soccer fields” to the more modest and specific 13 fields, the economic engine aspect of the project has faded and the City’s argument for the complex has shifted to “it won’t cost too much to operate.” And you can kiss those “national” tournaments goodbye.

The December 16, 2009 briefing for the City Council hails the original 2003 estimates of operating revenues and expenses for the proposed sports complex as conservative—read “low-ball”—then turns around and makes wildly liberal estimates of operating expenses and revenues, starting out with a 100% utilization scenario that shows (surprise, surprise!) a net profit of $330,000 a year—if the as-yet-unfunded $17.2 million Phase B is built.

An optimistic 100% utilization? No one’s going to believe that. Even at 75% utilization and lighting on all but three fields, the City only stands to make $23,688 a year according to their own numbers. If we talk apples and apples, at a conservative 50% utilization the complex loses from $226,000 and $303,000 annually depending on whether Phase B is built and how many fields are lighted. At that rate, the City will probably be turning the project over to Salt Lake County (as it recently did with its Sorenson Unity Fitness and Recreation Center) just about the time the grass has grown in—that is, if the County is willing to take over a second soccer complex.

{quotes align=right}What happens if, or when, this becomes a commercial failure? Salt Lake City taxpayers will probably end up paying off the bond—which, of course, will cost a good deal more than $15.3 million, owing to the wonders of compound interest.{/quotes} We will be the owners of 13 soccer fields outside of the reach of all but the most ardent soccer parents, to be sold to some well-connected developer for a song. Is this is what the legislature envisioned when it sold off the state parklands?

Money is an object. Your property tax bill is the direct result of hundreds of programs like this. Many of them, perhaps even a soccer complex, are worthy of our tax dollars. But to put good money after bad, to saddle Salt Lake City taxpayers with $15.3 million of debt when property valuations are declining, is nothing less than fiscally irresponsible.

The city’s Fact Sheet, upon which the City Council bases its education, states that “very few” sites meet the criteria for a soccer complex. Not a single alternative site is mentioned.

Who decided to put all the eggs in the Jordan River basket?

Save Our Jordan, a coalition of citizens not in favor of soccer fields on that site, has identified five alternatives, all of which would be accessible to more citizens. A couple would make good brownfield restoration projects, including the two mentioned by Søren Simonson.

Certainly, a series of improvements, perhaps even enlargements, of mini-soccer complexes around the city would serve most of the soccer community better than the Tundra Tourney Fields now envisioned. How about a Transit Tourney that takes place on two or three remote but closely TRAX-connected sites? Transportation options for the soccer complex on this site are miserable. Adding insult to injury, after driving 50 or so blocks just to get there, soccer chauffeurs may then be expected to participate in the “revenue-based activity” of paying for parking.

If a soccer complex on this site is half as successful as projected, the effect of all those team-sized vans and SUVs may need to be factored into the City’s air quality studies.

{quotes}Envision Utah’s Blueprint Jordan River establishes three levels of riparian area protection based on the Bronze, Silver and Gold awards at the Olympics. The City admits that this land has the potential for “silver” level preservation and restoration. Does any other City-owned riverfront land qualify for this distinction?{/quotes}

Envision Utah’s levels, rather than qualitative, are based on a quantitative measure—simply the size of the buffer zone. A true measure of riparian value would take into consideration floodplains, groundwater recharge, vegetation drip lines, plant communities, topography, stream morphology, in-stream flows and erosion coefficients, gaining sections (where water seeps into the river), soil types, meander corridor. This piece of property really has the potential to become a platinum riparian area if Salt Lake City really believes in the vision it embraced when it signed on to the Blueprint Jordan River.

In 2003, a slim majority of Salt Lake City voters said we were willing to spend $15.3 million for what was hoped to be a 25-field soccer complex, about $600,000 per field. We did not agree to spend $1.2 million per field. We did not say we wanted it located on the last of the Jordan River’s riparian shores. To claim otherwise on either point is disingenuous and downright manipulative. If a new site can’t be settled on by the end of this year, the matter should be put to a new bond vote for the entire amount needed.

Mayor Becker has interesting and exciting plans for making Salt Lake known for its environmental progressiveness. Here’s a great opportunity for his administration to step up and own a green future. The soccer complex can go almost anyplace. The Jordan River has only one option.