Green-aids in the fight against urban blight.

by KRCL's Radioactive

Envision an empty urban plot – a gathering place for garbage and neglect. This is property that somebody owns but nobody cares about. This is a space in many city neighborhoods that gives nothing and gets nothing. Until you come along. With some creativity, hard work and community support, a vibrant garden appears, offering a place to enjoy and share. A place with shade, flowers, birds and butterflies and perhaps even some organic veggies. How does this transformation take place? The land is there, the need is there, all the project needs is you, and maybe a couple of friends ready to create your own first guerilla garden.

Envision an empty urban plot – a gathering place for garbage and neglect. This is property that somebody owns but nobody cares about. This is a space in many city neighborhoods that gives nothing and gets nothing. Until you come along. With some creativity, hard work and community support, a vibrant garden appears, offering a place to enjoy and share. A place with shade, flowers, birds and butterflies and perhaps even some organic veggies. How does this transformation take place? The land is there, the need is there, all the project needs is you, and maybe a couple of friends ready to create your own first guerilla garden.

David Tracey, author of the new book "Guerilla Gardening: A Manualfesto," is the executive director of Tree City, a Canadian ecology group focused on caring for the urban forest. Recently, Salt Lake's community radio station KRCL interviewed him for their "RadioActive" program.

RA: David, this book really gave me a lot of joy. What is guerilla gardening? What does that mean?

DT: There are a lot of different definitions because there are a lot of different people doing it. If you go out and plant beyond your property line, whatever that might be, you are a guerilla gardener. But for the sake of having some definition, I call it gardening public space, with or without permission.

RA: What inspired you to write this book?

DT: It was really about the environment and bigger picture things. The small picture was just seeing that empty lot and thinking it would look better with flowers. And since nobody else is doing it, maybe I can. But the bigger picture is really the way the world is going. I read the news, I listen to the reports and it's dire. I have friends who are almost on the edge of checking out – they think it's way beyond us, we can't handle this thing anymore. I used to think I could go and escape somewhere – but now we know that's not going to work. There is no more escape. So I figure we have to turn and face it. And the place we take our stand has to be in the cities. We are now a city species. We are an urban animal. More than 50% of the planet's population lives in cities. Unless we get together and figure out new ways to design and live in the cities of the future, what hope do we have?

RA: You mention in the book that the city is one of our crowning achievements, but that it's really underutilized.

DT: I'm really ambivalent about cities. I have a love-hate relationship. There are a lot of great things about cities, but at the same time, they can also be pretty horrid places for the environment, for social degradation and all the negative stuff you see. Both the challenge and the opportunity is focused in the city.

RA: You mention the use of space that isn't necessarily public, but that could be utilized as public.

DT: What is public space? It's not exactly determined. The classic definition is the places we all own – where anyone can go and do anything legal and not get permission. The public space I am looking to guerilla garden is actually wider than that. I like to take an ecological definition. Because now we know that all of our spaces are connected. {quotes align=right}Whether the title or deed says that one property ends right here and six inches over is another property, doesn't really mean much to the natural world.{/quotes} When I look at those public spaces I look at them all as spaces we share environmentally. And in that sense, if it's a public park or a bank planter box, if we can improve it with plants, I think we should.

RA: And that transforms the actual experience of the people in the community around it.

DT: That's the key. The real public space we are after is the one between the ears. It's our consciousness and what we think. There has been a real shift over the past 20 to 30 years from public to private. We used to have a pretty good sense of what public space was and what we all owned together. But nowadays with video surveillence and the way corporate entities are moving into the areas we thought were shared and taking them over for their own purposes – people are confused. We've really lost our sense of what we as a community share. We need to take those places back.

RA: Frequently you walk past a vacant lot and you see weeds and trash and a lot of people think somebody owns that, so I can't do anything. How do you begin to make a guerilla garden?

DT: An example of one in Vancouver is pretty much the situation you are talking about. In the inner city—in an intensely bad area where all the social problems roll into one, there was an empty lot filled with trash, condoms, needles—all the detritus of our urban problems. Our group wanted to take it over. So they looked for the owner, searched the city records but couldn't find him. In true guerilla garden fashion they went in and planted it anyway. And lo and behold, as things started to grow the owner showed up. The owner had a curious reaction, a two-sided response. On the one hand, he felt violated because it was his land. But the owner had two sons—one involved in landscape architecture and the other in homeless advocacy—who said it was actually a great opportunity. They set up a contract for the guerillas to lease the land from the owner with the agreement that whenever the owner wants to take the land back the guerillas will leave. In the meantime, they are running a community-supported farm. It worked out fabulously, all because they started as guerilla gardeners.

RA: We all have this inherent tie to natural space and the cycles of living.

DT: We really do have it inside us. For millions of years, we were plant people. {quotes}We had a profound relationship with the natural world, and it's only in the last 100 years that we've lost it.{/quotes} We don't understand the natural cycles anymore. We've lost touch, but we get it back when we start working again with the earth. Something inside just feels right. You go into a hypnotic state. It's DNA calling us back through our ancestors.

RA: I think too that it builds empathy for other living things beyond human beings.

DT: Connection is the word. Start to think of your city not just as grids, or traffic patterns or zoning areas, but really as a habitat. Think of it as an urban forest. It's a complex and beautiful place we live in.

RA: You have a recipe for seed grenades.

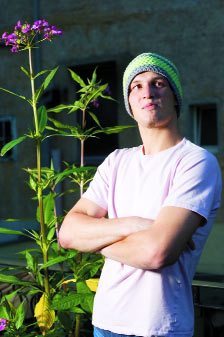

DT: Those come from the Green Guerillas in New York. They started in 1973 when a woman named Liz Christy was in the Bowery, walked by an abandoned lot with a lot of trash in it. She saw a refrigerator with a child trying to crawl in it. The mother appeared and Liz yelled at the mother, "Why don't you do something about that?!" And the mother yelled back (in true New York fashion), "Why don't you do something about it?!" And so Christy got friends together, cleaned up the lot, replanted it and started a movement which became the Green Guerillas. Now they are a huge organization with community gardens all over the city. One of the things they came up with, because a lot of these spaces were fenced off, was the seed bomb, or hand "green-aid." It was a way to get wildflower seeds in a small lobbable packet. You just make a ball with mud or clay and mix in wildflower seeds until it hardens enough to throw, and you're done. When the ball hits ground on the other side of the fence, it breaks open and spreads the seeds.

RadioActive airs live M-F at noon on KRCL 90.9 FM. You can stream the entire interview at www.krcl.org.