The environmental cost of cheap clothing

The scene is familiar. You go to your nearest fast fashion retailer to purchase some new clothes. You see racks and racks of identical shirts, pants, blouses and dresses in various sizes. You browse the selection while poppy and upbeat music plays on the loudspeaker. You decide on an item and head to the check-out. You wear your new purchase for the first few times without worry. But with each journey through the laundry the quality fades. Even more troubling for those who follow fashion, your new purchase quickly becomes the outdated. In a matter of months you’re no longer wearing the hottest trends.

What do you do? Based on statistics, you toss it in the garbage. Or you donate it to a thrift store. In a short while you’ll head back to the retailer in search of a new purchase.

But thinking of clothing as disposable, and acting like it is, comes at a cost. The fashion industry is widely considered to be one of the most polluting industries in the world, second only to the oil industry. Our hunger for constantly new clothes, and our habit of discarding things after very little use, poses enormous environment and ethical problems.

How fashion gained speed

Fast fashion refers to an approach to fashion that emphasizes cheap and quick retail that reflects the changing trends of the season. The first large increase of scale in the fashion industry happened in the 1800s after the Industrial Revolution and after the first sewing machine was patented. These changes produced a significant drop in the cost of production and the textile industry boomed.

Around the end of World War II, large clothing factories outnumbered home seamstresses and small workshops. In the 1960s, truly cheap, trendy, mass-produced clothing became available. With the large factories in business and Baby-Boomers becoming old enough to have spending power, the cost of clothing dramatically dropped.

Now, fast fashion giants like H&M, Zara, Forever 21 and Express are in the business of producing cheaply made clothing that won’t stay in style for long. The former four seasons of fashion are now 52 “micro-seasons.” According to Forbes, the average consumer today purchases 60% more clothing than just 20 years ago and people are keeping these clothes only half as long.

Oil, flame retardants and pesticides

Look at the tags on your clothes. If the materials listed aren’t silk, wool or other long-lasting and, frankly, more valuable and expensive materials, it’s probably not made to last. In addition to being designed for disposal it’s probably made with greater environmental costs than you might imagine.

The most popular fiber used in fast fashion is polyester. Polyester fiber is made of petroleum, a nonrenewable resource. Yes, your polyester clothing began in an oil well.

Each year, 70 million barrels of oil are used to produce polyester. (That’s enough oil to fill 70 million standard American bathtubs.) These clothes have all the related environmental issues associated with this extractive industry.

And since polyester is flammable, a flame retardant is often added to the fabric, which increases its toxicity. In washing, polyester clothing sheds microfibers small enough to slip through water treatment plants. Over time, this increases the amount of plastic in our oceans, where it can harm aquatic animals. It takes 20 to 200 years for polyester to decompose.

Cotton, which makes up almost half of the world’s fiber production, is advertised as an ethical fabric but it, too, has environmental consequences. Cotton crops account for 11% of all pesticides used in industrial agriculture and 24% of insecticide use. Pesticides and insecticides are added to the commercial crops. We all know by now that many pesticides contaminate water, endanger fish and honey bees. Bats, too, are vulnerable to pesticides.

Your clothing is under water

A whopping 5,000 gallons of water is used to produce just two pounds of cotton—think jeans and a t-shirt. That’s about how much water one person drinks over a course of three years. Now picture how many t-shirts are hanging on the racks of just one fast fashion location. According to a 2017 Pulse of the Fashion Industry report, the industry used enough water to fill an Olympic sized pool 32 million times.

The chemicals used to make the popular fiber viscose (also known as rayon) include sodium hydroxide and carbon disulfide. The rivers near the villages where rayon is produced, in China, India and Indonesia (there are no producers of viscose in the United States), often turn black from the chemicals. And the problem with rayon isn’t just a problem of water. Workers in viscose-producing factories have shown unusually high rates of heart disease, stroke and nerve damage.

Slow fashion: a shopping alternative

Much like the changes many of us have made with our food choices, fashion when chosen carefully can be slow, fair and even organic.

Let’s start by doing away with the idea of disposable clothing. Each year Americans toss 14 million tons of clothing. The first step in ending this cycle is to buy clothes that last. Think of your parents’, or maybe even your grandparents’, old coats, dresses and slacks that likely are still hanging somewhere in a closet. It is possible to still find clothes that will last. The trick is to buy less and buy more thoughtfully.

Buying natural fabrics can help you avoid many of the environmental costs associated with fast fashion. Look for clothing made from hemp, linen, silk and wool. Bamboo and organic cotton are better alternatives than conventionally produced cotton (with organics you cut out the use of pesticides) but toxic chemicals are still used to turn these organic products into fabric.

This may be a challenge now. But as more consumers demand ethical, slow fashion, more options will become available. The list of fair, eco-friendly retailers is growing. Some of them you’ve probably heard of (Patagonia and Eileen Fisher); many of them you probably have not (Indigenous and Outdoor Voices). Many of these companies manufacture their clothing in the United States or are certified fair trade and child labor-free. Tradelands, based in California, makes blouses for women with natural and sustainable and recycled materials. Yireh, in Hawaii, produces just a small line of clothing products in Bali and pays their workers fair wages, including paid vacation and sick leave. (For a list of 35 sustainable retailers go to thegoodtrade.com/features/fair-trade-clothing)

Lots of us aren’t prepared to spend $100 on a shirt. Luckily for us there’s another eco-conscious option. Imagine if we could “recycle” those 14 million tons of clothing that get thrown out every year. Keeping these clothes out of the landfill, according to the EPA, would be equivalent to taking 7.3 million cars off the road. Well, the good news is we can do this. It’s called thrifting.

Thrifting and consignment

Lightly worn clothing can be given a second chance. Donating to and shopping at thrift stores, consignment shops and secondhand retailers is a best practice when it comes to slow, sustainable fashion. It should be an easy step. But not many of us are doing it. The Council for Textile Recycling estimates only 15% of clothing gets donated; the rest ends up in a landfill.

There are loads of great places locally for secondhand shoppers. Savers is a global thrift retailer with over 300 locations—the first store opened in an old movie theater in San Francisco’s Mission District, in 1954—and Savers stores can be found in and around Salt Lake. “Reuse is our reason for being. In the last year alone Savers helped divert more than 700 million pounds of reusable clothing and household goods from landfills,” says Chad McBride, store manager of the Savers Millcreek location (3171 E 3300 S). The reasons to thrift and second-hand shop are clear for McBride. “Each time consumers buy new, they’re exhausting the environment of those resources. Every time those items go to the landfill, so do the resources that went into creating them. The cost of our clothing is more than what’s on the price tag.” New off-the-rack clothing has a high cost for the environment and for consumers, McBride points out. “Second-hand shopping is an easy and affordable way for people to lower their overall footprint—and score unique fashion finds at 70-90% of the regular cost.”

Salt Lake City-based Deseret Industries (with stores in seven Western states) is a local favorite. Opened by Elder John A. Widtsoe in 1938, one of the guiding purposes at the DI is to help reduce waste. What doesn’t get sold to customers in Utah gets donated through humanitarian aid projects.

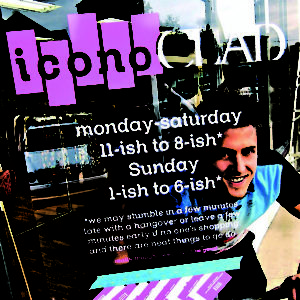

A local consignment store that is making a difference is iconoCLAD (414 E 300 South). Tom Sobieski, a former insurance executive looking for a new life, opened the store in 2014. He says he always loved treasure hunting, which led him to thrift shopping. “Going to a thrift store was always very thrilling.” He urges those who think thrifting is beneath them to start focusing on what fast fashion is doing to the environment.

The environmental impact of fashion is important to Sobieski and the rest of the staff of iconoCLAD. He describes thrifting as “a form of entertaining environmentalism” and a way to lessen environmental impacts. Sobieski also points out the additional waste generated—cardboard, plastic, textiles and paper—with clothes bought online.

Properly cared for clothing is important to consignment stores. Sobieski says iconoCLAD focuses more on the condition of the clothing than of the brand. “We’d much rather take an exciting low-end brand that has been well taken care of than a high end brand that’s been damaged in a dryer on high heat.”

Clothes that are not sold in Sobieski’s store are donated, primarily to the Other Side Academy, a Salt Lake-based nonprofit that offers vocational programs as an alternative for those facing long-term incarceration and others seeking serious lifestyle changes. The Other Side runs a thrift store of its own at 4290 S. State St.

Besides iconoCLAD, Sobieski recommends other local consignment stores Uptown Cheapskate (now a national resale chain that originated in Utah), Name Droppers and Unhinged.

New does not always mean better. New means adding to an already existing and serious problem. We express ourselves through our clothing, but the Earth should not have to suffer as a result. If you’re looking for a cleaner way to clothe yourself, consider taking up thrifting and second-hand shopping. There are many treasures to be discovered.

Fast fashion might seem harmless but it’s a dangerous cycle. If you believe you won’t love and wear a piece of clothing two months from when you purchase it, be mindful of why you’re choosing to buy it now.

Additional ideas for restoring balance in the closet

Have a clothing exchange!

If you’re looking for a way to score some new clothes while fine-tuning your own closet, have a clothing exchange! Camron Park, an organizer of a local clothing exchange that has been meeting twice a year for about six years, shared her tips on how to put on one of your own.

Park says all you need for a clothing exchange are guests and the clothes they want to swap. Snacks and drinks are nice additions, but to keep the food away from the clothing. Put many mirrors in the room of the exchange. Consider having your exchange in the fall or spring, since many people clean out their closets during transition seasons. Park says she and her roommate got the idea for a clothing exchange when they realized their closets were full of items they weren’t wearing anymore. “We figured if we had closets full of still great clothes we weren’t wearing, then our friends must too. We really weren’t expecting our clothing exchange party to become a twice yearly tradition among our friends but we’re really happy it has.”

For Parker, one of the many pleasures of clothing exchanges is seeing clothing passed from one friend to another. New life is breathed into clothing that was previously just hanging in a closet. Other benefits include not having to spend time and money shopping for clothes, keeping clothes out of landfills, and building a community of friends. Parker says the clothes that are left over at the exchanges are donated to charities.

Clothes last longer with proper care

It’s likely that, when clothing was more expensive, people took better care of their clothes by hanging them up after wearing, replacing popped buttons and repairing their shoes. Dresses often had “armpit shields.”

With frequent washing in a machine, microfibers can shed, loose embellishments on clothing can become tangled and damaged, tiny tears can become larger and fibers can weaken. Dryers can also break down fibers (think of what’s in the lint catcher!). Additionally, dryers can shrink and stretch clothing.

The obvious sometimes bears repeating:

- Follow the proper care instructions on the tag of the garment.

- Use “delicate’ cycles whenever possible; overwashing can often fade color and wear fabric.

- Machine wash delicates in a mesh bag.

- No need to wash jeans after every wear, they last a long time between washes.

- Line-dry clothing whenever possible.

- Wash and dry seasonal clothing before storing to prevent moths.

- Organize your laundry according to color and the temperature of the water in the wash.

Taylor Hawk is a senior at the University of Utah, majoring in English and a CATALYST intern.