In light of recent events, the topic of environmental justice is finally gaining traction. Here’s where we’re at in Salt Lake City

This, the first of three articles on environmental justice in Salt Lake City, focuses on the the way things are right now. In upcoming issues we’ll discuss how we got to this point and what we can do to mitigate current issues.

Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, income or national origin with respect to developing, implementing and enforcing environmental laws, regulations and policies, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

This means there should be no differences in terms of environmental exposure across populations—i.e. the air that wealthier people breathe should be the same as the air less wealthy people breathe; noise pollution should be the same across all neighborhoods regardless of race, and so on.

We all know that is not the case. Poor neighborhoods suffer the most environmental degradation.

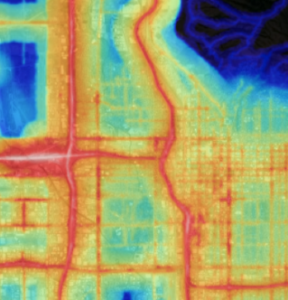

Take noise pollution. Airports, large highways and industrial facilities tend to be fairly noisy and may sometimes operate at all hours (as can be seen in Figure 1). Since property values near these noise polluters are lower than around quiet areas, lower income (which generally means higher minority) populations live in these locations.

Take noise pollution. Airports, large highways and industrial facilities tend to be fairly noisy and may sometimes operate at all hours (as can be seen in Figure 1). Since property values near these noise polluters are lower than around quiet areas, lower income (which generally means higher minority) populations live in these locations.

Historically, water pollution is also an important environmental justice topic, with wealthier areas putting forth resources and efforts to maintain cleaner streams, rivers and beaches. And light pollution is increasingly being studied as a factor in public health and quality of life.

However, the most apparent difference between wealthier and less wealthy neighborhoods regarding environmental justice issues is air quality.

Just drive to the mountains in winter and you’ll see the thick layer of pollution at the bottom of the Salt Lake Valley. While communities in the Upper Avenues, Emigration Canyon and Suncrest, to name a few, are above the inversion layer, communities in the western part of Salt Lake County have a grey pollution cloud hanging over them.

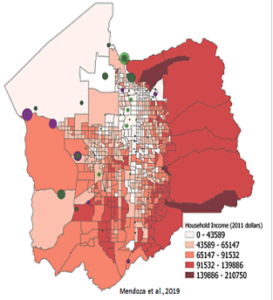

Geography has an important role to play, since pollution settles in the lower parts of the valley. But that is also where the largest emitters—factories, large highways—are generally located. These are also where lower-income and higher-minority neighborhoods can be found, as shown in Figure 2.

Geography has an important role to play, since pollution settles in the lower parts of the valley. But that is also where the largest emitters—factories, large highways—are generally located. These are also where lower-income and higher-minority neighborhoods can be found, as shown in Figure 2.

Dr. Robert Bullard, a sociologist often referred to as the “Father of Environmental Justice,” has written extensively on this topic. He’s found that the best determinant of air quality at the zip code level is the percent of minority population. These findings have spurred research on exposure to variable levels of air quality, the effect on children’s health and even the impacts from climate change.

We already know that elevated levels of air pollution negatively impact human health. In the 1990s, Dr. Arden Pope from Brigham Young University studied the correlation between air quality and Geneva Steel Mill’s intermittent closings. Recently, many studies are using more detailed air pollution measurements to learn about the impact of air quality on pulmonary outcomes, cardiovascular events, school absences and even suicide. These outcomes have been more acutely visible during COVID-19.

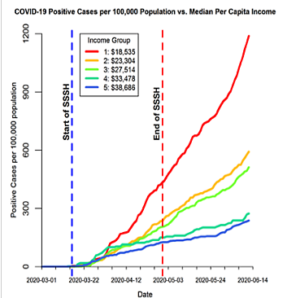

The pandemic is showing us stark differences across sociodemographic groups. A recent study found that the partial economic shutdowns and social distancing measures impacted communities in different ways. Workers in higher-income zip codes were able to work from home (or choose to not go to work) and reduce their exposure to COVID-19, as shown by lower traffic counts in Figure 3. Income and percent of white population were strong determinants in COVID-19 positive cases; the nearly 10-fold difference can be seen in Figure 4. These stark differences underscore the ripple effects of environmental justice on public health.

The pandemic is showing us stark differences across sociodemographic groups. A recent study found that the partial economic shutdowns and social distancing measures impacted communities in different ways. Workers in higher-income zip codes were able to work from home (or choose to not go to work) and reduce their exposure to COVID-19, as shown by lower traffic counts in Figure 3. Income and percent of white population were strong determinants in COVID-19 positive cases; the nearly 10-fold difference can be seen in Figure 4. These stark differences underscore the ripple effects of environmental justice on public health.

Daniel Mendoza is a Visiting Assistant Professor in City and Metropolitan Planning and a Research Assistant Professor in Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Utah.