![]()

by Katherine Pioli

Jobs, royalties and tax revenue vs. maintaining the integrity of one of the planet’s top avian habitats—or is there a third way? That’s the question state scientists must answer as Great Salt Lake Minerals plans an expansion of lake acreage that would equal the size of Salt Lake City.

It’s not easy for mineral extraction companies to earn positive attention, let alone support, of the environmentally-minded. But Great Salt Lake Minerals (GSL Minerals) knows exactly how to stay in good favor.

It’s not easy for mineral extraction companies to earn positive attention, let alone support, of the environmentally-minded. But Great Salt Lake Minerals (GSL Minerals) knows exactly how to stay in good favor.

It’s not easy for mineral extraction companies to earn positive attention, let alone support, of the environmentally-minded. But Great Salt Lake Minerals (GSL Minerals) knows exactly how to stay in good favor.

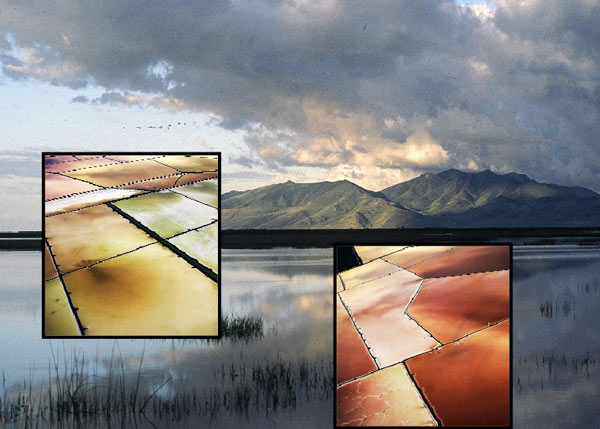

A subsidiary of Compass Minerals of Oberlin, Kansas, GSL Minerals has been extracting sulfate of potash (also known as potassium sulfate or SOP) from the north end of Great Salt Lake since 1967. Potassium sulfate is a fertilizer used extensively for food crops and lawns. GSL Minerals promotes their business of SOP mineral extraction as a sustainable process. They say they use clean energy, and work with habitat sensitivity to create an organically certified product that helps farmers produce foods.

To an extent, the company’s claims are true. The extraction process performed on the lake relies on solar evaporation to separate water from the desired minerals dissolved in the lake. The end product, the fertilizer, is USDA-approved organic. GSL Minerals likes to say that their fertilizer “is used by organic and conventional farmers who grow fruits, vegetables, nuts, and other wholesome foods to feed America.”

Recently, however, this environmentally sensitive image has soured. For the last year, GSL Mineral has sought to expand their operations on the lake by tens of thousands of acres-adding evaporation ponds, dikes and feed channels. Responding to this change, local hunting clubs, environmental groups, government biologists and others are beginning to see the company as a much less friendly industrial neighbor. And in the face of impending expansion, these groups wonder whether or not the lake will have a sustainable and healthy future.

Non-competitive exchange

The request for expansion, remembers former Division of Wildlife Resources avian biologist Don Paul, began innocently enough in June of 2008 when it came to the attention of the state leasing agency that GSL Minerals wanted to expand their evaporation ponds in Clyman Bay on the lesser-used northwest side of the lake. According to Paul, the agency saw a perfect opportunity to leverage some habitat protection out of an expansion deal. Although thousands of acres under lease since the 1960s were already developed in the Bear River Bay, thousands more remained undeveloped. If all the leases were to be used, says Paul, “it would leave just a narrow strip of flowing water, [basically] a river, against Promontory Point.”

The application submitted by GSL Minerals asked to lease 52,200 acres in Gunnison Bay. In its formal review of the application, the Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands wrote that it would consider “a non-competitive exchange of undeveloped lease acreage in Bear River Bay and acreage adjacent to Promontory Point for acres in Gunnison Bay.”

Based on this offer of exchange, the land swap was agreed upon in November 2008. As part of the swap 30,181 acres of “high habitat value sovereign lands lease by Great Salt Lake Minerals” would be exchanged for acreage on the west side of the lake.

“For me, at the time, the trade was a no-brainer,” says Paul. “My recommendation to others in the Division was to go ahead with the trade.”

What Paul and others did not immediately realize was that GSL Minerals had additional plans for expansion, plus plans to develop 8,000 acres of land already leased by GSL Minerals in the very heart of Bear River Bay.

GSL Minerals can’t seem to make up its mind, however. Although the Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands had approved the deal and the process had moved on to the Army Corps of Engineers environmental impact process, GSL isn’t satisfied. As we were going to press, it withdrew the application and submitted a new one with thousands of additional acres.

The new area requested totals over 118,000 acres.

These lands, especially those in Bear River Bay, are the part of a long-range development plan that worries environmentalists, biologists and recreationists. Lynn de Freitas is one of many people who do not want to see GSL Mineral’s industrial footprint mark such a vast area. Since 2002, de Freitas has served as executive director for FRIENDS of Great Salt Lake. The group works to preserve and protect the lake as a natural resource used by migratory birds.

For de Freitas, working on lake conservation has become a passion. So when she adds up the number of acres currently and potentially under development, she isn’t happy. ” If you translate that into more understandable terms, the potential size of the entire operation is larger than the area of Salt Lake City,” she says.

Furthermore, de Freitas questions the determination of the swap acres as “high habitat value” -that the lands GSL Minerals is giving up are in fact not nearly as habitat-crucial as the lands slated for GSL’s expansion.

What’s worse, the swapped lands aren’t necessarily protected. “Just because GSL relinquished leases doesn’t mean the state can’t just lease them right back-or lease them to someone else later,” de Freitas says.

For conservationists like de Freitas and biologists like Paul, the proposed size of the final expansion raises a number of concerns regarding water, avian habitat and public access. In short, they wonder if leasing all of this land is in keeping with the protection promised the lake by its status as a Public Trust Value.

Balancing the public trust value

The idea of a public trust value-a status given to the Great Salt Lake and other natural environments in Utah-is a bit tricky. Ultimately, the interpretation of its definition determines the management of the lake.

In this case, lake management falls to two agencies: the Utah Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the Utah Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands (DFFSL). As a Public Trust Value, the lake’s management plan requires these two agencies to provide protection and balanced access to the lake’s many uses, including that the agencies “encourage development of the lake in a manner which will preserve the lake, encourage availability of brines to lake extraction industries, protect wildlife and protect recreational facilities [navigable waters such as those in Bear River Bay].” It directs the agencies to “encourage the use of appropriate areas for the extraction of brines, minerals, chemicals and petro-chemicals to aid the state’s economy” but at the same time to “maintain the lake and the marshes as important to the waterfowl flyway system.”

Managing Great Salt Lake thus becomes a huge balancing act- pleasing industry and the state economy while appeasing environmentalists, protecting habitat and maintaining the scenic values for tourism and recreation. And each group seems to have their own idea about how and where that balance is best found.

For the state of Utah in a time of economic need, industrial expansion assists with balancing the budget. Currently, GSL Minerals brings 330 jobs to Utah. The company estimates 50 more jobs would be created by the expansion. GSL also pays more than $2 million in annual property and sales tax and more than $3 million annually in royalties. The expansion would bring an additional $5 million per year to the state in tax and royalty payments. So, for Great Salt Lake Mineral, the state of Utah and the people employed by the company, expansion is a move toward balance.

Dave Hyams, senior vice president of media relations for GSL Minerals, likes to explain how his company’s expansion is also a necessary attempt to balance production with a growing demand for fertilizer. “As our world population increases so does demand for food and demand for potassium sulfate,” he says. Already, Hyams reports, the company has tried to meet demand by increasing efficiency and production with existing resources. “We are attempting to increase production on our current footprint and investing in technologies-like new covered conveyor belts-to reduce product loss during stages of production,” he says.

But, $40 million worth of efficiency improvements later, demand still exceeds production. Hyams sees development in the requested areas as inevitable and natural-simply a balance of supply and demand. “But I see people calling for the entire operation to be shut down,” he says. “That doesn’t seem like balance to me.”

For groups like FRIENDS of Great Salt Lake, the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge and the Utah Waterfowl Association, balance means finding an equilibrium that will sustain life on the lake and the lake’s shores. The Great Salt Lake is, after all, one of the most important aquatic habitats for birds in western North America. Don Paul likes to describe the shallow pool of salty water as “a Route 66 gas station for birds traveling along the migratory pathway from Mexico the Canada.”

The Bear River Bay in particular, with its unique mix of saline water and fresh flows (from the Weber, Ogden and Bear Rivers), is an extraordinarily valuable avian habitat. Countless eared-grebes, nearly 50,000 tundra swans, Canada geese and hundreds of other species make the cattails along the banks their home. Paul uses the Canada geese to illustrate exactly what this habitat means for the waterfowl: “The geese lose their feathers and become flightless for a couple of weeks. They chose that particular site in the Bear River Bay as their home for that vulnerable period because it has good food sources and enough space to escape easily from predators.”

Paul acknowledges that the birds continue to make Bear River Bay their seasonal home and have even with the current evaporation ponds. But imagine, he invites, what the bird colonies might look like without any industry confining them. Then, he adds, imagine what it will look like with even more development and less space for habitat.

Death by a thousand cuts

“I am not against industry,” Paul says with all seriousness, though at the same time he admits that as a biologist he prefers to err on the side of wildlife. “But we forget what has already happened,” he says. For instance, the high prairies in central Wyoming, once open rangeland for sage grouse and migrating herds of antelope and elk, are now fragmented by oil rigs and wind farms. “All of these little piece slicing away at our natural resources eventually ends in death by a thousand cuts,” Paul says.

Lynn de Freitas sees clearly the possibility of this death. It is not only the cut from the Bear River Bay that she worries about, but also the expansion proposals for the west side of the lake. Of particular concern is Gunnison Island, which hosts the second or third largest population of American white pelicans in all of North America.

For these pelicans, the lesser used habitat on the west side of the lake is key. Though the birds find their primary food source-fish-in the fresh waters on the east side of the lake they prefer to nest 35 miles away on Gunnison Island. “They know that they are protected out there,” says Paul. Protected, that is, as long as the lake water remain high enough to keep out curious humans and other predators. During a low lake event in 1963-the lake was shallow enough to allow a person to wade miles out to the island-human intrusion led to the deaths of many young pelicans. The current expansion proposal has the ability to once again lead to similar occurrences. “By lowering the level of the lake waters we make these birds more vulnerable,” says Paul.

While it is difficult to prove the effect of additional evaporation ponds on the lake’s levels, changing the composition of the lakebed could prove as harmful as threats to the water’s depth. Currently the lake’s surface sits 4,194 feet above sea level, only three feet above the record low. But, as de Freitas points out, this will probably change. “Historically the water in the lake functions with a flowing equilibrium. This ability to breathe is key to maintaining avian habitat. By dyking shorelines you lose that capacity,” she says.

De freitas asks how new evaporation ponds, even on currently exposed lakebed on the west side, will affect the lake’s natural ability to rebound when high waters come again. “In those low lake level years it looks like there is no life and no vegetation. But just add water and things come back,” she explains. “There are brine shrimp pockets that are able to survive under the harshest of conditions on the shoreline for years that, when the conditions are right, open up. Put evaporation ponds on the lakebed and those brine-concentrated, uninhabitable conditions will remain the same regardless of what may happen to the open waters on the rest of the lake.”

The deciding line

So there are the arguments: boosting local jobs through expansion verses maintaining current size and navigable waters for hunters and recreationists; giving fair and equal presence to valuable industries on the lake verses protecting one of the last and most important avian habitats in North America. Where does one find balance? Where does one draw the line?

Dave Grierson, ecosystem manager coordinator for the Utah Division of Forestry, Five and State Land, claims to know the answer, literally. “If you draw a line from Promontory Point down through Antelope Island, east of that line, with the notable exception of the existing Great Salt Lake Minerals ponds, is all designated for protection. The areas west of that line are determined suitable for salt extraction, oil and gas and brine harvesting,” he says.

When it comes down to making decisions about management of the lake, says Grierson, it’s easy-the decision has already been made. For 10 years (from 1997 to 2007) the lake’s governing agencies worked on developing a management plan-the same that designates the lake as a Public Trust Value. This document guides Grierson’s handling of issues such as GSL Mineral’s request for land. “I am not making decisions when I decide to lease land to companies like GSL Minerals, I am following the plan. I need to follow it, according to the law,” says Grierson.

As of last December, and now as of this June, the governing agencies have gone ahead with permitting additional lands on the west side of the lake to GSL Minerals. The only thing keeping GSL from excavating their ponds now is a final environmental impact study being conducted by the Army Corps of Engineers. They will look at three laws: the Clean Water Act, the Rivers and Harbors Act (identifying impediments to navigation) and a marine protection law. Grierson says they will be studying bird colonies such as the snowy plover and the American white pelican to determine if any significant harm will occur to habitat and nesting. They hope to complete the studies by the end of this year.

What have we come to?

As Lynn de Freitas says, this could be a deciding moment for the future of this unique aquatic ecosystem. “If we continue to compartmentalize this lake system, many authorities feel that it could be compromised to the point that sustainability of habitat will be very uncertain.”

But the final word has not yet been spoken and there remain some opportunities for alternative directions. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is helping the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers review the potential impact of the industrial expansion on wildlife. In a formal letter, Larry Crist, Utah Field Supervisor for the Fish and Wildlife Service, has expressed certain reservations and concerns about the project.

Of primary interest to the Fish and Wildlife Service is reconsidering the 8,000-acre development planned in Bear River Bay. In defense of that space, the letter says the Service has “provided comments to the Corps describing the remarkable value of Bear River Bay for migratory birds.” They recommend that the 8,000 acres in Bear River Bay also be relinquished, which would eliminate many of the wildlife concerns with the existing proposal.

The US Army Corps of Engineers is taking public comment on the new application three times this month before it moves on to the next stage of drafting the environmental impact statement.

Recognizing the possible proximity of new ponds to Gunnison Island, the Fish and Wildlife Service has also recommended that “any environmental analysis consider the entire project area and consider impacts to the breeding colony of pelicans on Gunnison Island.” Fish and Wildlife also calls for a cumulative impacts analysis including one that takes into account effects of lake level changes.

These cautionary notes from a government agency closely involved in the process of approving industrial expansion gives hope for those looking for a solution weighted towards habitat preservation. With critical eyes such as these-possibly assisted soon by the Great Salt Lake advisory council, a group organized by Governor Huntsman to represent industry, environment and public interest in the future of the lake-the sustainable and continued existence of Great Salt Lake, and all the creatures who have come to depend on it, many indeed be possible.

Katherine Pioli is a staff writer for CATALYST except in the summer when she is a forest firefighter in Wyoming.

Public comment and scoping meetings:

June 4, 5-8p. Davis County Library, 725 S Main St., Bountiful.

June 9, 5-8p. Comfort Suites Hotel, 2250 S 1200 W, Ogden.

June 11, 5-8p. West High School, 241 N 300 W, Salt Lake City.

Questions: 801-295-8380, x14.