Your past, spoken or unspoken, is carried in your blood

I was kidnapped when I was three months old. My 24-year-old mother left me lying on the front lawn of our Salt Lake City apartment at 1157 East 3rd Avenue and went inside to fetch something. When she returned, I was gone.

Frantic, she searched everywhere. Beautiful Mama in her silk cheongsam in 1953, fresh out of Oakland Chinatown asking for help in perfect English. She must have been quite the sight. Hours went by. Daddy was called home from work. The neighbors joined the search.

Dusk was falling. Other mothers, worried a kidnapper was loose in the neighborhood, bolted home to check on their own kids. The lady next door came back in a panic—her kids were gone, too! Now everyone was searching not just for me but three other little girls as well.

Finally they found us in a neighboring garden shed, playing on a blanket. There I was, cooing happily away, surrounded by toys and three little girls. They’d never seen a baby like me before and thought I was a doll.

I played with those little girls every day for the first three years of my life. The eldest girl was concerned that I wouldn’t be able to go to Heaven with them. The way she talked about it, it sounded like an amusement park so I really wanted to go. She said it was a shame but I was too dark. Not knowing what she meant, she put her forearm next to mine and that was the first time I noticed the color of my skin.

There we were, two little girls who loved each other: her worried that we would be separated in the hereafter and me wondering what was wrong with the color of my skin and if I could fix it somehow so we could play together in Heaven.

I am the first nationally recognized Asian Pacific Storyteller in the United States. I’ve been all over the world and told a lot of stories but I never thought the most amazing story I’d ever tell would be my own.

My name is Brenda Jean and I was born at St. Mark’s Hospital, delivered by a tiny four-foot-tall chain-smoking female doctor. Dr. Toshiko Toyota must have brought the entire Japanese community of Salt Lake into the world.

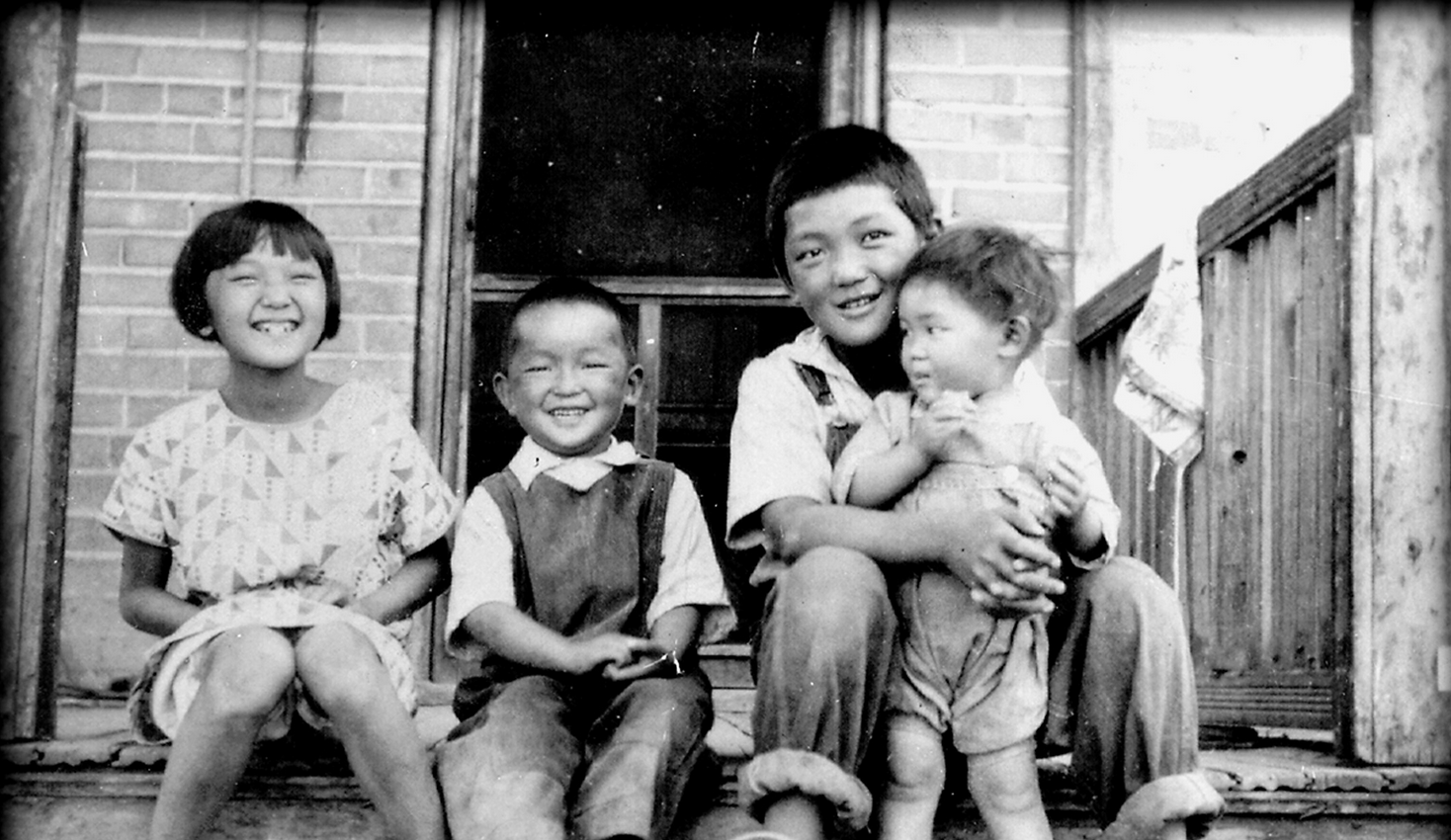

My father came from a family of 11 orphans, ages infant to 18, all raised by the eldest, my Aunt Sets. My father was the star quarter back for West High. My cousins were the youngest ski patrols. My Uncle Sam became a decorated war hero. Aunt Sets was a pillar of the Japanese Christian Church.

When I was three, my father joined the Navy and we moved to California. But we still came to Salt Lake for holidays. Aunt Sets was the Oneesan and I was the Oneesan so I had a particular affinity for her. Oneesan means big sister and in a Japanese family it means you are responsible for everyone and everything and if anything goes wrong, it’s your fault because you didn’t prevent it. The Oneesan is supposed to take care of the family until everyone dies and only then can you have a life of your own. At least that is the way it was in our family.

Aunt Sets worked in the candy packaging department of Associated Foods. I went with her one time and played under the table where I could listen to all the ladies in hairnets gossiping and eat the candy that fell off the trays. At home, she was in constant motion, cooking, embroidering, crocheting afghans & making christening clothes for everyone’s babies. She sang Shigin, a form of chanting to ancient poetry. Why none of us ever thought it was strange that Aunt Sets sang Shigin, I’ll never know. All we knew was that Aunt Sets would sing that weird Japanese stuff at family gatherings and hush! Don’t make fun!

Aunt Sets married late in life, waiting to make sure her younger siblings were old enough to take care of themselves. But she felt so guilty about moving to California she said it was no surprise to her that the bombs dropped when she got married.

Literally. She married on Dec. 7, 1941—Pearl Harbor Day. She spent her honeymoon sleeping on hay and whitewashed manure in a horse stable at the Tanforan Race Track near San Francisco, then was eventually shipped out to the Topaz Prison Camp in Delta, Utah. When her brothers and sisters came to visit her they said, “Gee Neesan, if you’d stayed here with us, you’d be on this side of the fence.”

Prejudice against Japanese after the war was at an all time high in California. Aunt Sets and Uncle Dave’s Oakland grocery store had been confiscated during the war, so they returned to Utah where Uncle Dave worked for Morton Salt and stamped the Morton Salt logo on all the big bags of salt 40 hours a week. He tithed to the LDS until the day he died because he said the only whitemen who would give a Jap a break were the Mormons.

Most of my aunts and uncles stayed in Salt Lake, so I had plenty of cousins. They can all hunt, fish, ski and ride, even the girls. I was scared of them. Still, they were patient with me and I learned to ride horses.

Summers in Salt Lake were the best! Racing my horse in the canyon with my cousins early in the morning before it got hot and coming back to Aunt Sets’ house at 175 North Redwood Road for country breakfast spread outside on a picnic table on a blue and white checker table cloth was heaven! Homemade biscuits with butter and preserves she’d put up herself, eggs and bacon. Her big blue kitchen always had enough food to feed an army. All Aoki family gatherings took place there.

In 1989, I received a grant from U.S. Congress to document the impact of the Japanese Incarceration on my family.* Strangely enough, I discovered that except for Aunt Sets, none of my aunts and uncles had been incarcerated. As my father said, “Why would we need to go to camp? We were already in Utah!”

The Aokis come to Utah

The Aoki clan was one of the earliest Japanese families in Salt Lake, arriving in 1909. Orphaned within a few years, the children sensed there was something different about them, and that feeling was passed down to their children as well. What was it?

I experienced this firsthand upon meeting my husband’s uncle. He said, “You’re not an Aoki from Salt Lake are you? That bunch of wild things?! Everybody knows them. But hell, they couldn’t help it, they raised themselves.”

And why were we in Salt Lake City in the first place? I asked Aunt Sets since she was the eldest but all she said was to go talk to her elder cousin Sadae, whom she called her Oneesan.

At this point, I’d been living in San Francisco for about 10 years. I visited Sadae in Sacramento. She was 103 years old. She told me, “Our family has lost face and our loss of face affects our children and our children’s children.” She said she was not going to die until our story was told—a story I had no inkling of:

My grandfather, Chojiro Aoki, was the first to come to this country in 1897, sent by the Meiji Emperor to start the first Japanese settlement in America—Japantown San Francisco. He was selected because we were a high-ranking Samurai family descended from Emperor Tenchi (626-772 AD) and had lived by Aoki Lake in the Shinano Mountains for centuries.

Mentored by the Archdeacon of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, Grandpa became one of the first full ordained Japanese Christian priests. Around the time of the 1906 Great Earthquake, Grandpa’s little brother Gunjiro met and fell in love with the Archdeacon’s daughter, Helen. Their announced engagement ignited a scandal in the press and caused the California State Assembly to hold an emergency session to block their marriage by passing a bill preventing Japanese from marrying Caucasians in the state. (Many newspaper articles about Helen and Gunjiro can be found in the San Francisco public library.) So Gunjiro and Helen got married in Seattle. The Archdeacon was so angry at Grandpa for not stopping the marriage, he sent him to Utah to convert the Mormons. And that’s how the Aokis got to Salt Lake.

Grandma was a registered midwife. She and grandpa traveled to mining camps delivering babies and preaching the word. But she soon died of pneumonia; she was still nursing the baby. Grandpa died a few years after—of humiliation, maybe. The 11 children were left alone to be raised by their 18-year-old Oneesan, my Aunt Sets.

At the outbreak of World War II, most West Coast Japanese got rid of their family scrolls because they were afraid of being associated with Japan. Because my family was under less scrutiny in Utah, we kept ours. Armed with the family scroll and a photograph of our family crest from the kimono Sadae wore on the boat coming over here in 1903, I went to Japan and with the help of a graduate student from the University of Nagoya, I found the Aoki ancestral home and visited the Aoki graves.

Sadae passed when she was 110. I like to think because our story had been told that we’d regained our face. By then I had performed Uncle Gunjiro’s Girlfriend, with my husband and son, all over the world.

Aunt Sets sure could keep a secret! She knew this story all along but her father had charged her, as the Oneesan, to never tell her younger siblings who they were because, “Shikata ga nai”—nothing can be done about it. He had been sent by Emperor Meiji to start the first Japanese settlement in America! He was vested with a very important quest and failed. How shameful!

But what I learned is that your past, spoken or unspoken, is carried along in your blood. The Aoki Clan in Salt Lake has always been known to be a little cocky, outside the box, willing to take risks. All Grandpa did was stand up for his brother’s right to marry whomever he loved, even a white girl! Aunt Sets could sing Shigin! Centuries of samurai blood runs in our veins!

I’ve been a storyteller for over 42 years now and what I know is that when we die, all we leave is a story. The story of the Aoki Clan in Salt Lake all began with a love story. The rest is history. Now I can pass on to my son what Aunt Sets told me: No need to lower your head, the Aokis are an honorable family.

Brenda Wong Aoki is a San Francisco-based performance artist and story teller. She will keynote the May 2 Mountain West Arts Conference, Utah Cultural Celebration Center. 8:30a-4:30p. Conference is $55-$110. .

* After Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcing the removal of 120,000 people of Japanese descent, two thirds of whom were American citizens, into prison camps. Stripped of their Constitutional rights, these people lost everything—their homes, businesses, assets confiscated and incarcerated for up to five years without due process. At the end of the war, when the camps closed, the internees were given a train ticket and $50 to begin a new life in a hostile world. My husband’s mother was in Poston, my Aunt Sets and Sadae were in Topaz.