Have you ever wondered about that cheerful upside-down basket that represents the Beehive State? Everyone recognizes it as a beehive, but I can bet you’ve seen it only on Utah Highway Patrol cruisers, the Great Seal of Utah and a lot of old Salt Lake City buildings. The skep hive, as it is called, was chosen as the Utah territory’s symbol in the 1840s by Brigham Young.

For the last 150 years, however, bee-keepers have housed their little friends in sensible square boxes, not the skep. Our official imagery hasn’t quite kept pace—but why did we stop using the skep, and what did bees live in before it?

Left to their own devices, Apis melliflera, the European honeybee, will create nests in hollow trees, rock cavities or caves. A related bee species also creates free-hanging combs off cliff faces in Nepal, where locals of the splendidly named Bung Valley use smokey fires and rope ladders to harvest the wild honey.

The advent of beekeeping occurred over 4,000 years ago in ancient Egypt, where people learned to keep bees in clay cylinders—a practice that still goes on, little changed, today. We also find evidence of clay cylinder or hollow-log apiculture 3,000 years ago in the Near East. The technology of the skep came along about 1,000 years later.

So the skep is an ancient symbol, part of our culture for some 2,000 years. The sensible square boxes—”Langstroth hives” —that are almost exclusively used today, were not invented until the middle of the 19th century.

While the skep is far more visually pleasing, it presents some major functional limitations to the beekeeper. The two principal of these are that the honeycomb can’t be easily inspected for signs of disease, and that the bees were often injured or killed outright in order to harvest the honey. While some skep methods spared the bees, most simply did away with them by fumigating the hive with burning sulfur. Skep hives are now actually illegal in many U.S. states.

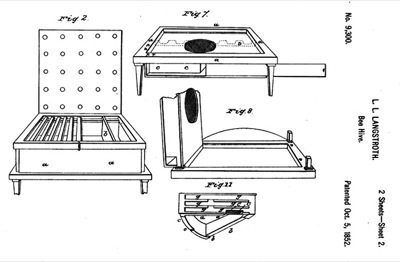

The Reverend Lorenzo L. Langstroth came to the rescue of the humble honeybee in 1860 when he patented his eponymous hive. Langstroth is credited with the discovery of “bee space”—this is a fairly precise measurement: the width of a cranny in which bees will move around, but will not attempt to either build comb across or seal with propolis. The frames of a Langstroth hive are calculated to be a “bee space” apart, keeping them free-hanging from the sides of the hive, easily removed for inspection or harvest. With a “queen excluder” mesh inserted into the hive, the brood comb is easily restricted to the lower levels of the hive, making honey harvest far less damaging to the bees.

New interest in beekeeping has recently spurred development of other kinds of hive, e.g. the WBC hive, the Dartington Long Deep, the Beehaus, the Long Box, and the top-bar hive. There are even hives now designed for bumblebees. The Langstroth, however, still reigns supreme among practical apiculturists.

And the lovely skep? I’m afraid that until someone can design one with removable frames it will remain against the Salt Lake City ordinance to keep bees in one, but we’ll still be seeing its shape in official imagery for a long time to come.